Health sciences education has long focused on the science of teaching, but in recent years we have seen a shift toward the science of learning [1, 2]. This study focused on undergraduates’ workplace learning in health sciences education [3,4,5] from an educational psychology perspective. Psychological theories, especially the theory of self-regulated learning (SRL), focus on the individual learner and view learning as a process in which cognitive, motivational, emotional, and contextual aspects are considered [6,7,8]. To gain a better understanding of undergraduates’ learning processes at the workplace, multivariate and longitudinal studies are needed. Such studies require fewer items per construct, which helps avoid survey fatigue and increases applicability in workplace settings, especially stressful ones.

We assessed the psychometric properties of single-item measures of constructs related to self-regulated learning at the workplace and this paper discusses the items’ role in health sciences education research. We selected some single items from the Workplace Learning Inventory in Health Sciences Education (WLI) [9] scales and specifically developed others using more general wording.

Self-regulated learning in the workplace

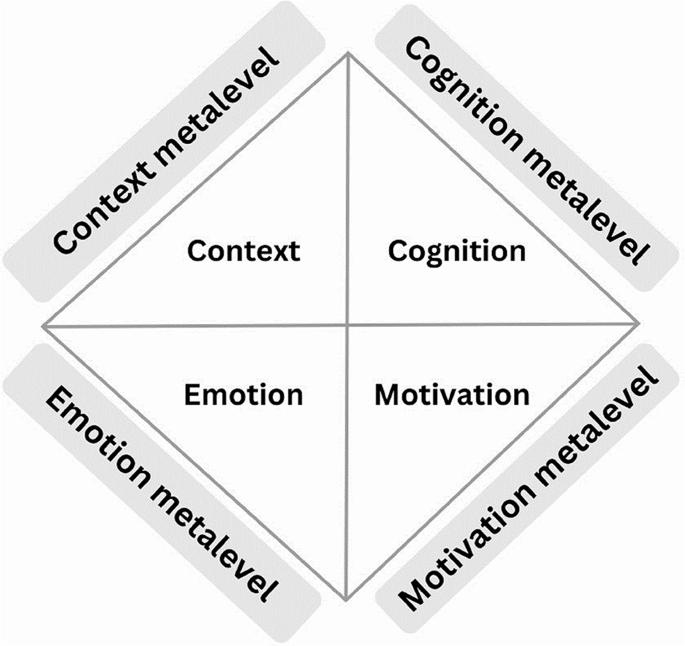

The study was based on SRL research [10, 11]. In health sciences education, the most prominent SRL theory is a process-based model, namely Zimmerman’s cyclical phases model, which differentiates between the forethought, performance, and reflection phases [12, 13]. Besides process-based models, there are also component-based models that integrate different areas (e.g., Pintrich’s conceptual framework for assessing motivation and SRL) [14] and levels (e.g., Boekaerts’ six-component model of SRL) [15]. The present study adopted Steinberg et al.‘s [9] component-based model as its conceptual framework. The model integrates four areas, namely cognition, motivation, emotion, and context, at two levels, namely the learning process level and the metalevel, resulting in a total of eight components (see Fig. 1).

The four areas of workplace SRL at the learning process level (inner components) and the metalevel (outer components), based on Steinberg et al. [9]

Cognition refers to learning strategies focused on workplace learning [16]. Motivation means instigating and sustaining goal-directed activity [17]. Emotions are defined within the broader concept of affect but are distinguished from other affective phenomena, such as moods, in that emotions are more intense, have a clearer object focus and a more salient cause, and are typically experienced for a shorter duration [18,19,20]. Context means undergraduate medical students’ perceptions of multiple dimensions of the educational environment in the clinical practice setting [21]. The metalevel of cognition, motivation, emotion, and context means regulating those respective aspects of the learning process [14, 22,23,24,25]. For more details on the model, we refer to Steinberg et al. [9].

Steinberg et al. identified aspects relevant to the eight components of undergraduates’ workplace learning and developed corresponding scales, resulting in the WLI [9], which provides 31 scales, each comprising three to six items. Researchers investigating workplace learning can select the scales that are relevant to their research questions. Table 1 lists the constructs with their corresponding definitions.

Van Houten-Schat et al. [13] and Roth et al. [26] reviewed SRL research and respectively identified the need to investigate SRL sub-processes in the workplace to gain a better understanding of the interplay of the different SRL aspects, as well as the need to use more diverse methodologies in SRL research, including multivariate longitudinal and diary studies. Single-item measures of the WLI constructs could facilitate such studies.

Single-item measures

We summarize the discussion on the advantages and disadvantages of using single items in scientific studies, based on overviews provided in the literature [27,28,29]. Arguments in favor of the use of single items include parsimony, which is relevant in holistic studies considering the large number of theoretical constructs, as well as in diary studies with many measurement points and in time-limited settings such as data collection in the workplace. Parsimony is also associated with increased participant motivation and cognitive involvement, resulting in fewer missing values and higher validity. Moreover, parsimony addresses researchers’ ethical commitment to participants; that is, researchers strive not to overburden participants and to avoid their confusion and frustration when answering similar items. Other arguments in favor of the use of single items are their lower ambiguity, better interpretability, higher face validity, and reduced risk of criterion contamination.

Arguments against the use of single items include their lower or unknown reliability, their inability to adequately capture complex psychological constructs, and the less fine-grained distinctions between individuals. Hence, single items are usually acceptable when the construct is concrete, unidimensional, clearly defined, narrow in scope, and used as a moderator or control variable or when the desired precision is low [27, 28, 30]. Fisher et al. summarized successful examples of single items used in organizational psychology [28].

If there is uncertainty about whether a construct meets the above requirements, validation tests can be performed to ensure trustworthiness [30]. The appropriate validation method depends on how the item was developed, that is, whether it was selected from an existing scale or developed anew [28]. For items selected from a scale, Gogol et al. [29] have provided the following best practice for examining the psychometric properties: [27] assessing the reliability, information reproduction, and relationships within the nomological network. For newly developed single items measuring stable characteristics (or traits), the recommendation is to assess the test–retest reliability [28]; however, this method is inappropriate for single items measuring states that are expected to change over time, as in longitudinal studies [31]. To provide evidence of the validity of newly developed single items, assessing relationships within the nomological network is recommended.

Aim

Our study aimed to examine two sets of single items appropriate for research on undergraduate health science students’ learning by analyzing their reliability, their correspondence to the full scale, and their relations with external criteria. These sets of single items could be helpful for economically conducting multivariate longitudinal and intensive longitudinal studies in health workplace settings. First, we investigated 29 single items selected from the WLI [9]. The items address four areas of workplace learning, namely cognition, motivation, emotion, and context, at two levels, namely the learning process level and the metalevel. Each of the eight components is represented by several items, with the exception of emotion on the learning process level since Duffy et al. [20] have already provided single items for that. We systematically compared the single items with their corresponding full scales with respect to the following measurement questions [29]: (1) How reliable are single-item measures? (2) How well do single-item measures reproduce the information that the full scales obtain? (3) How well do single-item measures reproduce the relationships with external criteria in the nomological network that the full scales obtain?

Second, we examined four newly developed and more generally formulated single items measuring states rather than traits [32]. The items represent cognition, motivation, emotion, and context at the learning process level. Although their reliability cannot be tested, we examined the items’ validity with respect to the following measurement questions: (1) How well do single-item measures correlate with their respective full WLI scales? (2) How well do single-item measures relate to external criteria within the nomological network?

link